Peek v Wheatley [2025] NSWSC 554

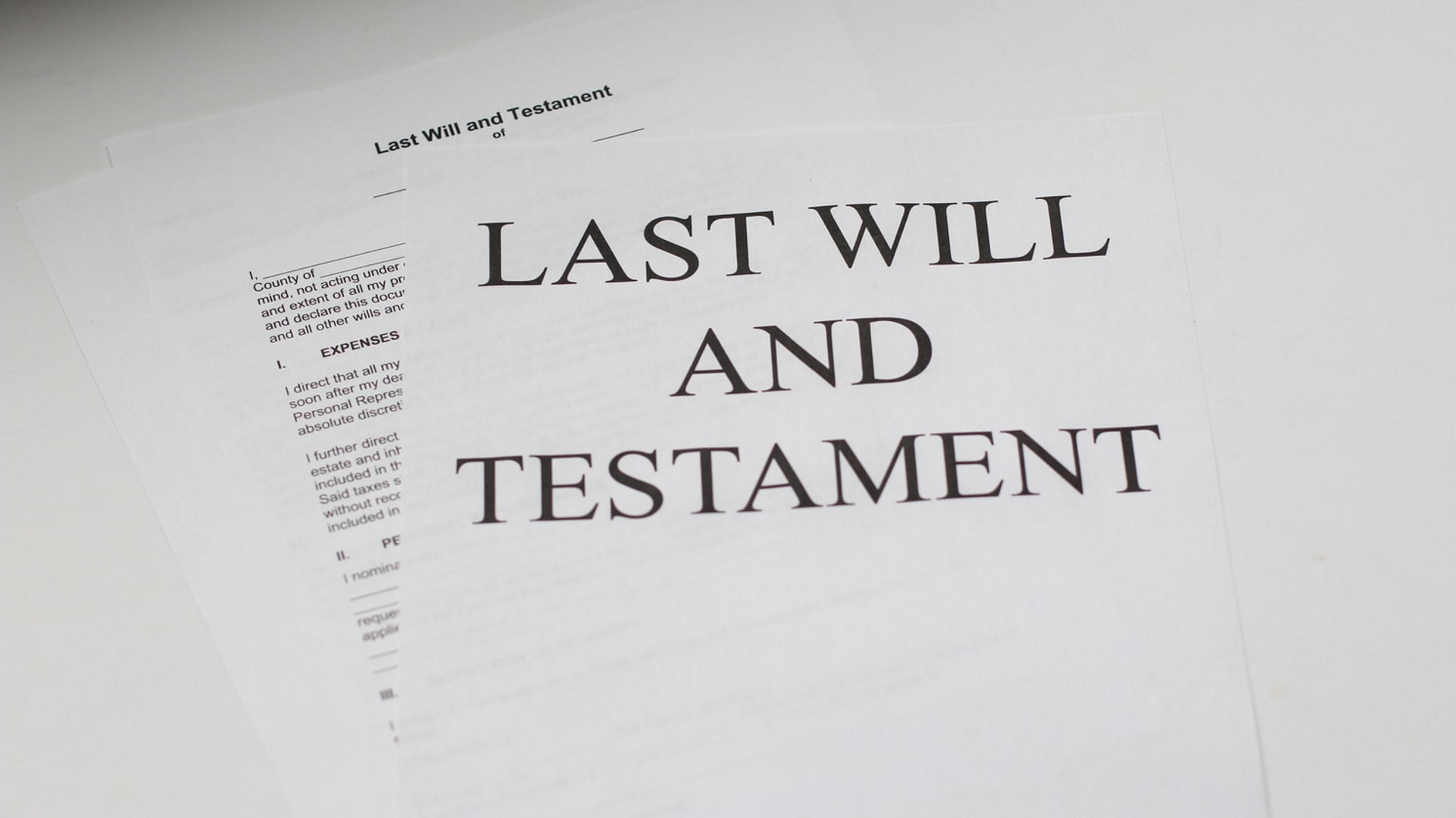

In the matter of Peek v Wheatley [2025] NSWSC 554, the Supreme Court of NSW recently had to consider whether an informal document found in the “Notes” application on the iPhone of the late Colin Laurene Peek (the “deceased”) should be admitted to probate as an informal will under s 8 of the Succession Act 2006 (NSW) (the “Act”).

Section 8 of the Act enables the Court to dispense with the formal requirements for the execution of a will where that document:

- purports to state the testamentary intentions of a deceased person; and

- the Court is satisfied that the person intended it to form his or her will.

The Court heard that the informal document was discovered after the deceased’s death by the deceased’s solicitor at the deceased’s home while he was there searching for an original will of the deceased. No original will executed in accordance with the formal requirements was found.

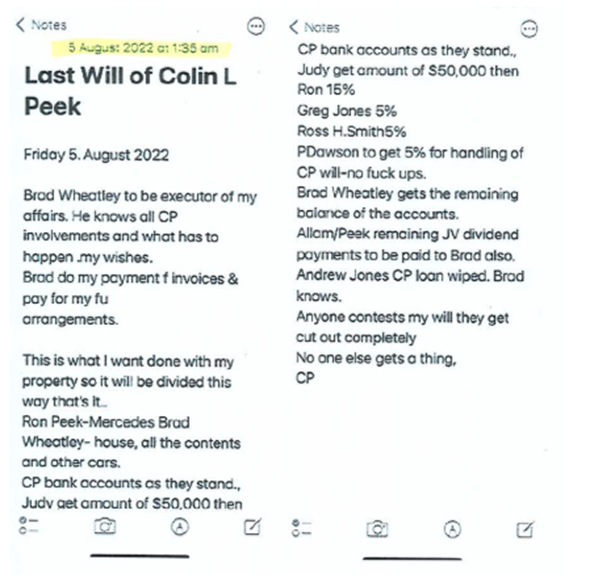

A copy of the informal document is as follows:

The net value of the deceased’s estate was approximately $13,600,000.

The plaintiff (the deceased’s brother), submitted that the Court could not be satisfied that the informal document, without more, was intended by the deceased to have legal effect as his last will. In the event that the informal document was not admitted to probate, in circumstances where no other will for the deceased has been located, and where he did not leave any spouse, children or parents, the plaintiff (as the only sibling of the deceased), would be entitled to receive the whole of the deceased’s estate pursuant to intestacy.

The defendant in the proceedings, a friend of the deceased, stood to benefit significantly from the informal document and was represented in the proceedings by the deceased’s former solicitor who had a personal interest in the proceedings (he was a beneficiary under the informal document) and he was a material witness in the proceedings (having been the deceased’s solicitor and friend, having been in contact with the deceased around the time the informal document was drafted and having been in the deceased’s home when the informal document was found). Due to this conflict, the Court considered that the probative value of all of the evidence of the witnesses for the defendant was affected.

There was no dispute that the document purported to state the testamentary intentions of the deceased. The main issue for the Court to determine was whether the deceased intended this document to have “present operation as a will”.

The Court noted the observations of Mahoney JA in Estate of Masters (decd); Hill v Plummer (1994) 33 NSWLR 446 that “There is, in principle, a distinction between a document which merely sets out what a person wishes or intends as to the way his property shall pass on his death and a document which, setting out those things, is intended to cause that to come about, that is, to operate as his will. A will, like, for example, a contract, a deed, and a sale, is, as it has been said, “an act in the law”.”

The Court also noted the comments of Kirby P in the same case that “A too stringent requirement of proof that a propounded document, otherwise clearly embodying the testamentary intentions of a deceased person, constituted his or her will would undo the reform proposed by the Law Reform Commission and accepted by parliament. Courts would continue to squirm at the results where the testamentary wishes of the deceased are sufficiently disclosed but cannot be given effect to because they fall short, in the court’s conception, of constituting the deceased’s “will”.”

The Court noted that notwithstanding the fact that s 8 is ‘beneficiary legislation’, “it is still necessary that the court is satisfied on the evidence that the document which is to be proved as the will was intended to be a will, rather than something which was brought into existence as a step towards the making of a will”’: Mahlo v Hehir [2011] QSC 243 at [40].

The Court found that the informal document had elements which both supported and did not support the idea that the deceased considered the document to be his will.

The Court made note of the following elements relied on in favour of the requisite intention:

- The heading, ‘Last will of Colin L Peek’ together with the date that he made the last change to it (5 August).

- It states ‘Brad Wheatley to be executor of my affairs’.

- His abbreviated initials (CP) appear at the end which is how he refers to himself in the document as his signature.

- It appears to intend to deal with all of his property by the statements: ‘this is what I want done with my property’; ‘it will be divided this way that’s it’; ‘anyone contests my will they get cut out completely’ and ‘no one else gets a thing’.

However, the Court found the following aspects went against the requisite intention for the informal document to form a will:

- There were some typographical errors in the informal document, and other elements such as punctuation errors suggesting informality.

- It stated: ‘P Dawson to get 5% for handling of CP will-no [expletive] ups”.

- The informal document did not in fact deal comprehensively with all the deceased’s property.

Perhaps the most determinative factor in the Court’s consideration was the expectation that, had the deceased meant for this informal document to be his will, he would have told his solicitor and the defendant, who was the executor and major beneficiary. This was not the case, notwithstanding he had ample opportunity to do so.

The Court further noted that there was difficulty in accepting the reliability of the evidence put for the defendant due to the conflict of the deceased’s solicitor acting for the defendant and in circumstances where it appears text messages had been deleted from the deceased’s phone at a time when it was in the possession and control of the defendant and the solicitor.

For the above reasons, the Court concluded that the deceased did not, without more on his part, intend for the informal document to have the present operation as the deceased’s will and accordingly declared that the deceased’s brother is entitled to Letters of Administration of the deceased’s estate on intestacy.

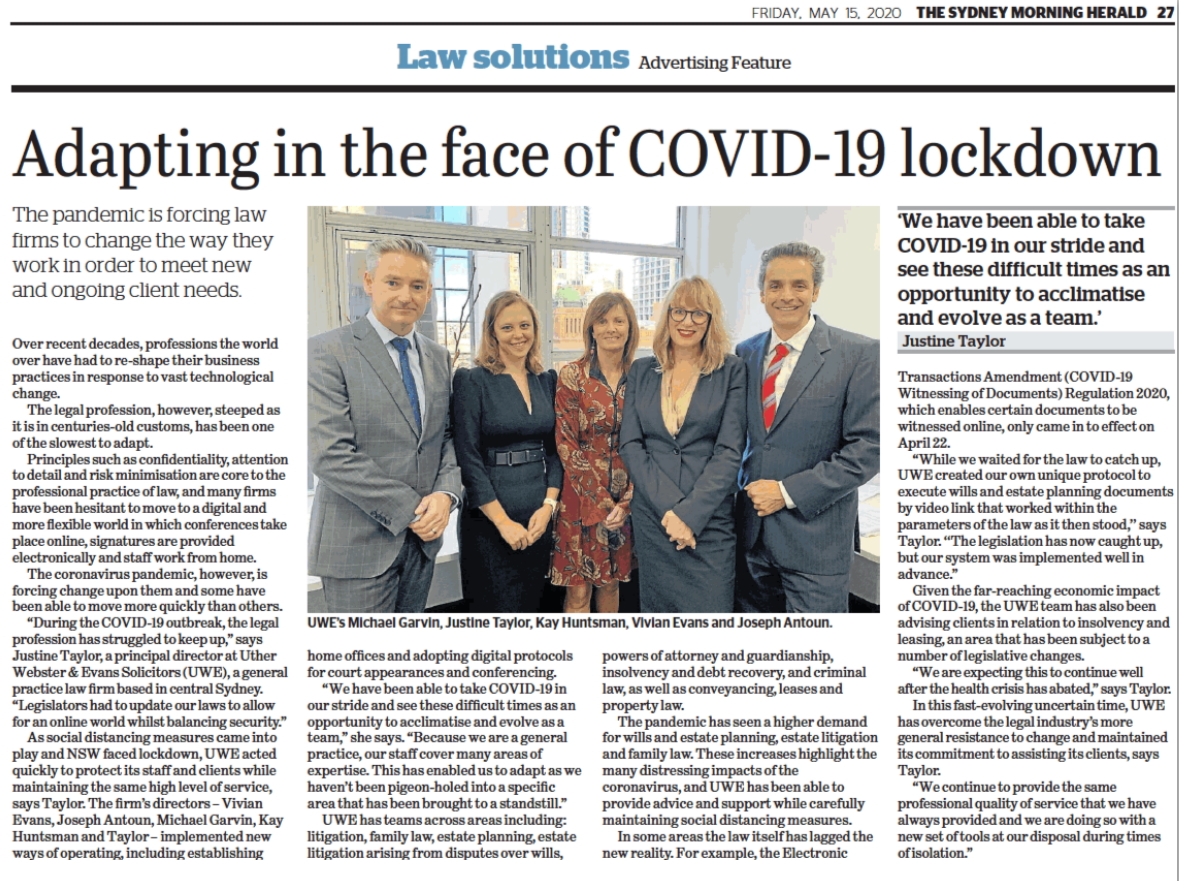

Navigating the legal and administrative steps in properly preparing and executing a will can be complex and this case emphasizes the importance of engaging a solicitor to assist with the process. If you need assistance in drafting, reviewing, or updating your will, our experienced estate planning team is here to help.